Differences in earnings between men and women have been a prominent topic in recent years. April 10 is the designated Equal Pay Day by the feminists’ National Committee on Pay Equity. The Committee erroneously states that women must work until April 10 to earn what men have earned the previous year.

No matter that the widely-cited raw median wage gap stood at about 18 percent in the most recent report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which would bring Equal Pay Day to the beginning of March.

That raw gap is explained by a multitude of contributing factors, including choice of college major, occupational choices, and hours worked. Moving beyond the raw figure and understanding the different dynamics at play is important in avoiding affirmative action for women that would introduce unintended consequences, such as reducing women’s hiring.

A recent working paper by a team of researchers from the University of Chicago, Stanford University, and Uber harnesses the rich data available for Uber drivers to shed light on what can explain the raw wage gap between men and women driving on the platform.

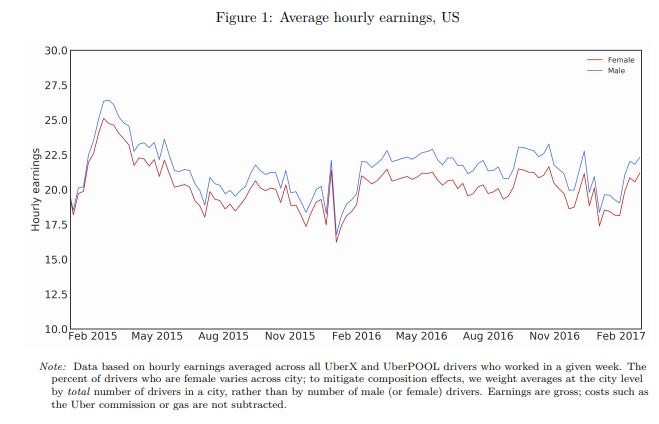

The team uses data from over 1.8 million drivers for the period between January 2015 and March 2017, excluding drivers for Uber services other than UberX and UberPOOL. They find that hourly earnings for male drivers are about seven percent higher than for female drivers.

Narrowing down the scope to people performing the same task on the same platform, and thereby removing the effects of occupational choice, significantly reduced the raw earnings gap. The nature of driving on the platform also removes the possibility for other channels of discrimination that might exist in other areas: drivers do not negotiate their wages and consumers cannot a priori discriminate against women drivers, as matching is determined by a gender-blind algorithm and earnings based on a formula using distance and trip time.

The authors also find that average driver ratings and cancellation rates are about the same for men and women drivers. They go on to claim that they “find no evidence that outright discrimination, either by the app or by riders, is driving the gender earning gap.”

If not discrimination, what is driving the seven percent gap in hourly earnings? To help answer the question, the authors focus on drivers in the Chicago metropolitan area. They find three factors can entirely explain the remaining gap: speed, experience, and driving location.

About half of the observed earnings gap is explained by differences in driving speed, as on average men drive 2.2 percent faster. As the authors note, driving faster has a positive expected return, as drivers could complete more trips.

Differences in experience come next and can explain about one-third of the gap. On average, men driving on the platform gain more experience. The 6-month attrition rate for men is 65 percent compared to 76.5 percent for women. As in other industries, experience can improve performance, as drivers with more than 2,500 trips earn about 14 percent more per hour than drivers with fewer than 100 trips.

Gender differences in where drivers operate can explain the remaining one-sixth of the earnings gap. Men drive in locations that tend to have lower wait times or higher surcharges.

In aggregate, and even in most single occupations or industries, the contributing factors that can be identified leave some of the observed earnings gap unexplained. It is notable, then, that the authors were able to completely attribute the earnings gap for drivers using the platform to these three factors.

The persistence of gender-based differences leads to raw gender earnings gaps, even within the context of driving for Uber, a flexible work situation devoid of many of the channels of traditional office-based discrimination. The continued existence of the gap, and that it can be completely explained due to differences in underlying factors such as driving speed, help highlight the need for a better understanding of the dynamics at play in other industries and the economy overall. The situation is not as simple as is sometimes portrayed.

This is not to say that as a society we should not continue to search for ways to root out channels of real discrimination or bias. For example, the researchers here suggest that Uber could make some adjustments and provide better contextual information to help drivers better understand and internalize the returns to experience, and this could alter driver choices, leading to a decrease in the observed wage gap.

Looking for a simple solution through the imposition of new legislation or regulations in an effort to completely eradicate any gaps in crude earnings is misguided and fails to address or consider what is driving those differences.

Charles Hughes is a policy analyst at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter @CharlesHHughes.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, E21 delivers a short email that includes E21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the E21 Morning Ebrief.