An impassioned argument has broken out during the last few weeks over the federal budget. It was precipitated by an op-ed piece in the Washington Post by five prominent economists from the Hoover Institution, warning of a coming debt crisis and pointing the finger of blame at runaway federal entitlement spending. A riposte appeared in the Post soon after from several prominent left-of-center economists, headlined “Don’t Blame Entitlements” and highlighting the role of tax cuts in worsening federal deficits. Since then several others have weighed in on the controversy, including my E21 colleague Brian Riedl, my Mercatus colleague Veronique deRugy, Jim Capretta, Ryan Ellis and a further rejoinder from John Cochrane, one of the original Hoover group.

The bottom line after all the back-and-forth: the Hoover economists and those who have written in support of them are correct (disclosure: I am a visiting fellow with the Hoover Institution but have not communicated with the Hoover authors about their op-ed). The budget problem we face is almost entirely an entitlement spending problem, and it is critically important to understand this reality if we are to devise effective repairs. For clarity, one must distinguish between three concepts:

- Whether we face a nascent fiscal crisis;

- What is causing that fiscal crisis;

- What we should do about it.

Fortunately for purposes of our understanding, both sides in this argument agree when answering question #1, that federal finances are in dire shape. The Hoover group finds that “unchecked, such a debt spiral raises the specter of a crisis,” while their critics agree that “growing debt will take an increasing toll on the ability of government to provide for its citizens.”

Naturally, there are strong disagreements over issue #3: what we should do about it. Those on the right generally prefer to restrain spending growth, whereas those on the left prefer to lean more heavily on tax increases. We need to hash out those policy differences, but it’s important not to let them confuse us about issue #2; the underlying causes of the problem.

Of course, there is a certain tautological sense in which one can always trivially define the budget problem as being equally one of taxes and spending, thereby implying that equal attention must be given to each when crafting solutions. After all, by definition the deficit is the difference between spending and revenues, so a $1 change on either side will affect the deficit by $1.

It does not follow from this, however, that both sides of the budget are equally or even comparably to blame for the problem. To understand why, simply imagine that each year you get a nice healthy raise, but that you nevertheless go more deeply into debt because your spending rises even faster. You might try to manage this problem by taking a second job or seeking a higher-paying one. This wouldn’t change the root cause of your problem-- your failure to moderate the growth of your spending. And unless you have a magic way of making more money every year forever, you can’t avoid the need to eventually restrain the growth of your spending habits.

With the federal budget, too, the problem is spending growth – specifically, entitlement spending growth. Entitlement programs are those in which ongoing spending is automatically authorized by law, without lawmakers needing to appropriate funds each year. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and other nonpartisan budget analysts have been documenting this runaway spending growth for some time. The federal fiscal imbalance is driven by that growth, especially in Social Security and the “major health care programs,” in CBO’s parlance.

One need not look for long at the contours of federal budget operations to see this. Consider tax collection patterns first. Figure 1 shows that nothing historically aberrant is happening on the tax side to bring about our huge deficits.

As Figure 1 shows, federal tax policy has been largely consistent throughout modern history--collecting between 16 percent and 19 percent of GDP in the vast majority of years. Even with the recent tax cut, this pattern is projected to continue going forward. Indeed, tax burdens will remain generally on the rise as a share of national economic output. In 2017 they were almost exactly at the historical average; now they are projected to dip somewhat lower in the next few years, then rise faster than GDP to climb above historical norms in 2024 and beyond. If we are facing a debt explosion, it is not because we’re eschewing taxation in any historically significant way.

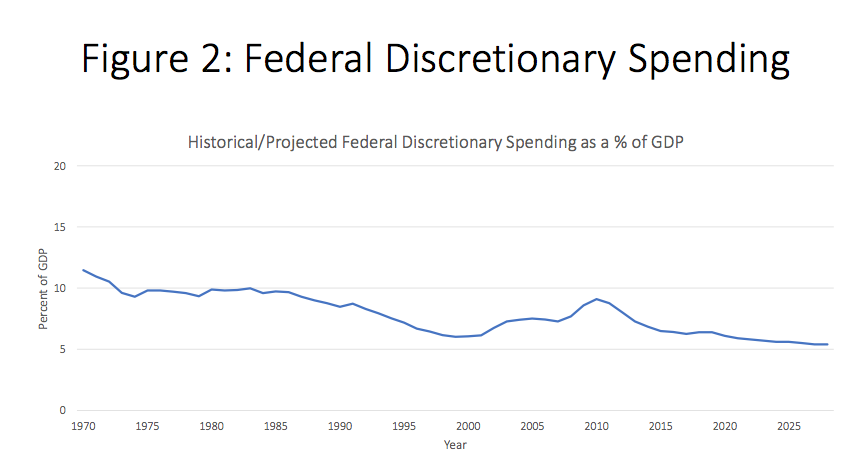

Nor, as figure 2 shows, is appropriated/discretionary spending the problem. Aside from a onetime surge in such spending early in the Obama administration, federal discretionary spending – including both defense as well as domestic spending – has steadily shrunk as a share of the budget and relative to our economic output.

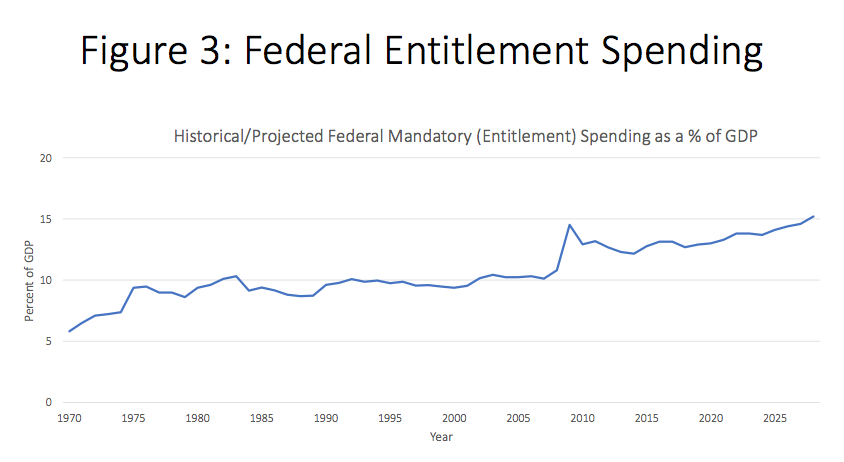

If national tax burdens have remained roughly consistent, and discretionary spending has become relatively more affordable, why have deficits climbed into the stratosphere? The answer is straightforward and is evident in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the source of our budget problems in a nutshell. They exist because year after year we are spending more on entitlements – not only as a share of the federal budget but as a share of our overall economy.

Some numbers from the latest CBO report amplify the point. There is wide bipartisan consternation over the latest CBO projections, which show annual federal deficits climbing from 3.5 percent of GDP last year to 5.4 percent of GDP by 2022. Yet entitlement spending alone in 2022 is projected to be 13.8 percent of GDP, and just the growth in such spending relative to GDP over the last few decades is larger than the entire projected 2022 deficit.

It is worth emphasizing that this way of measuring actually understates the point. All of these graphs and numbers are expressed as a percentage of GDP, which means they erase from the picture any growth in revenues and spending in step with national economic growth. If we instead showed the growth in real (inflation-adjusted) revenues and spending, entitlement spending would appear the culprit even more strongly.

Given the widespread evidence of the dominant role played by spending growth, why do some argue that tax policy is a comparable contributor to the budget problem? There are many reasons, but a couple that stand out are probably best described as analytical mistakes.

One mistake is to frame the question not in terms of the overall drivers of budget deficits, but in terms of policy decisions made only within a certain time frame. Tax cuts and appropriations increases do raise the deficit whenever they are enacted -- as they were last year -- even if they are not of a magnitude comparable to entitlement spending. So, if instead of asking, “What is driving the budget deficit?” we ask only, “What caused the deficit picture to worsen over the last year?” we are going to get a different answer: a distorted picture that reveals only a small fraction of the legislative decisions fueling our growing deficits, while ignoring all the others.

Excluding all policy decisions made outside a chosen time frame grossly exaggerates the relative effects of any decisions made within that time frame. While some might prefer to revisit policy decisions made during the last year to those made at other times, that subjective preference should not distort our understanding. To see the whole picture, one must look at all policies affecting the budget, not just those one is inclined to change.

The other mistake is to dismiss the primary drivers of the problem by treating them as unchangeable, while treating only some other policies as open to renegotiation. Hoover’s critics commit this mistake when suggesting that Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid benefits must inevitably grow more expensive because of “the aging of the population and the increase in economywide health costs.” They are mostly right in their analysis of the causes of program cost growth (though these programs are also delivering rising per-capita benefits), but theirs is only an explanation; it doesn’t undo the reality of the situation nor does it mean these trends cannot be moderated.

Current law implicitly makes various questionable policy choices; that virtually all of our improved national health and longevity should translate into greater fractions of our lives spent in government-subsidized retirement, and that government should fuel excess healthcare inflation by perpetually ratcheting up the amount of health services purchased through government-subsidized insurance. Some might see less political resistance to raising taxes than to moderating these spending policies, or they might simply prefer to leave them unrestrained. Either way, these programs are still driving the budget problem.

We need an open national discussion about whether to address the fiscal gap mostly by slowing the growth of government spending or by raising taxes. It is legitimate for anyone to argue that a certain amount of additional government spending growth is desirable and that we should raise taxes to meet it. This doesn’t mean, however, that spending increases are not driving our budget strains. Nor does it mean that we can continue perpetually to allow entitlement spending growth to outrun our capacity to finance it.

Charles Blahous, a contributor to E21, holds the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair at the Mercatus Center and is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, E21 delivers a short email that includes E21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the E21 Morning Ebrief.