If I left DC to drive to New York at 3p.m. today, Google Maps estimates that I would arrive in about 5 hours. Flying would take me about 50 minutes, plus the 2 hours or so required to get through check-in and security, and the time to get to and from both airports. Elon Musk claims he could get me there in 29 minutes with a new technology called Hyperloop, a pod travelling underground in a tunnel.

Musk’s vision is one step closer to reality because the State of Maryland has given his company permission to build a tunnel beneath the state-owned portion of the route. Maryland will not incur any of the expenses of building the tunnel. The federal government owns about two-thirds of the relevant land, and it is not clear where Musk’s company stands in terms of getting the go-ahead at the federal level.

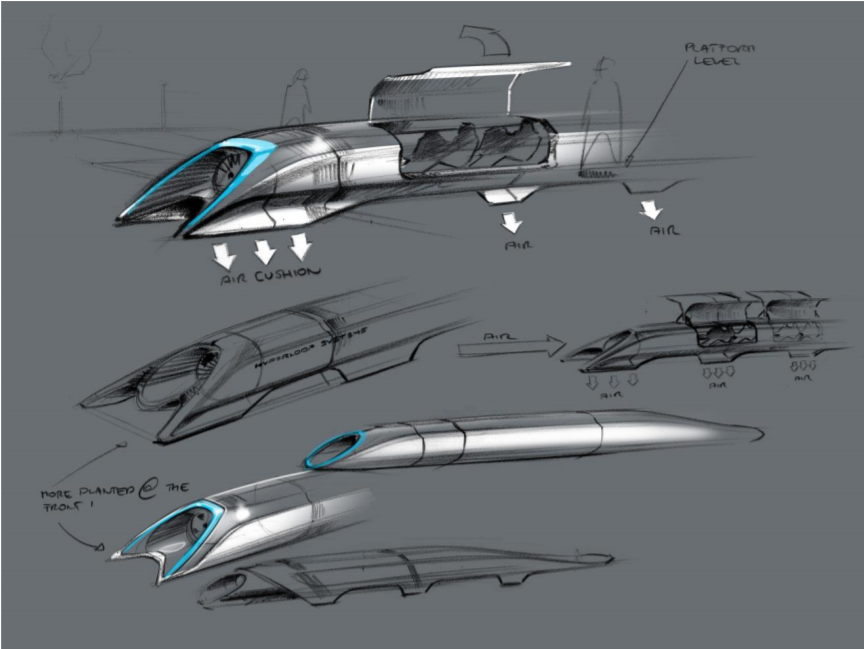

In August 2013, Musk released a design of Hyperloop, spurred by disappointment in California’s new high-speed rail. He outlined a small passenger train called a pod that travels in low pressure tubes. By eliminating friction and accelerating to 700 miles per hour, travel time from San Francisco to Los Angeles could drop from a 6-hour drive to a 30-minute Hyperloop ride. Other high speed rail options such as California’s high speed rail, which is still under construction, and Chinese bullet trains, have a steady speed of around 220 miles per hour.

Elon Musk’s Hyperloop Alpha Design

Source: SpaceX

Musk initially opted to open-source his idea instead of holding exclusive rights, allowing competition among companies to fulfill his vision. Unaffiliated companies such as Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT), Transpod, Arrivo, and Hyperloop One are working on the design.

Hyperloop One, formerly Hyperloop Technologies, the only company with an operational system, is the furthest along the path to success. Its design aims to use electricity to propel pods containing passengers or cargo. As the pod accelerates, it begins to levitate magnetically above the track. Hyperloop One has conducted two successful test runs on a functioning track.

Hyperloop One is working to meet its goal of 3 operational production systems by 2021. Hyperloop One has already begun discussing Hyperloop plans with various governments in countries such as the United Arab Emirates, India, and several others across Europe.

Hyperloop hopefuls must first address the regulatory limitation to Hyperloop construction Musk admitted in June that “permits [are] harder than technology,” so getting the Maryland permit is a substantial step forward. Permits would also be needed for Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and the federal government for the Washington-New York Hyperloop to be completed.

Another problem that needs addressing is who is going to support the costs of Hyperloop. Musk has a history of relying on government subsidies to help promote his visions. The LA Times estimates that as of May 2015, he and his organizations had collected an aggregate $4.9 billion in government subsidies in various efforts, including Tesla and SpaceX. This information is now outdated, as he has continued and completed additional expensive projects requiring subsidies in the last two years.

Canadian competitor Transpod estimates the cost of its prospective Toronto-Windsor Hyperloop will cost around $10.3 billion. This roughly 4-hour, 230-mile drive is comparable in length (and likely cost) to Musk’s proposed DC-NYC Hyperloop. A prospective Stockholm-Helsinki Hyperloop had a higher estimated cost of about $21 billion. While costs will differ due to length, region, etc., essentially all existing estimates for Hyperloop projects thus far dramatically undercut the roughly $68 billion needed for California’s high speed rail.

Further, while Hyperloop holds potential to transform the way people travel, it is unlikely to be built with private funds alone. If taxpayer funds are involved, it is vital that governments assess the significant risk of the investment. Transportation projects have a habit of overrunning their budgets. For example, the proposed California high speed rail system was estimated to cost between $33 billion and $37 billion. Now 7 years behind schedule, the cost continues to push upward towards taxpayer funds of $100 billion.

Ideally, Hyperloop would be funded by the private sector. The government has a role in funding basic research, but not in helping firms fund entire projects. While no transportation project of this scale has been completely privately supported, Amtrak is partially fiscally independent, which might suggest that it can be done.

As test runs continue to show promise of future growth and profit, Hyperloop projects might increasingly be considered a worthy investment for private investors. Perhaps companies would have to work at a loss until the system is operational, but that would not be a first. Amazon has netted very little revenue since its birth in 1997. It relies heavily on investors, and it prioritizes growth over net income. It was never a guarantee that Amazon would become the e-commerce giant that it is.

Hyperloop companies might see the greatest success by trusting the Amazon business model. If private investors, like Elon Musk himself, show their faith by investing in Hyperloop infrastructure now, the payout could be monumental in a few years.

Haley Skinner is a contributor to Economics21.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning Ebrief.

iStock Photo