Over at Bloomberg View, Conor Sen writes that critics of sky-high rents in New York and San Francisco have it all wrong: the unaffordable cost of living is actually helping the country by encouraging businesses to move to lower-cost cities. Sen acknowledges that restrictive zoning laws such as limitations on the height of buildings or the number of apartments a structure can contain keep the supply of housing low and prices up—but according to him, this is a feature, not a bug.

Sen’s argument proceeds along these lines: land-use restrictions in New York and San Francisco act as artificial caps on development in those cities. So high-tech startups in the Bay Area and financial firms on Wall Street will decide to relocate to low-cost cities such as Atlanta or Houston. This will enable the whole country to share in the fruits of economic development equitably.

The problem with this argument is that companies choose to locate in New York and San Francisco for a reason. These cities offer unique advantages to the industries that choose to locate in them, such as a common pool of workers trained in relevant skills.

Consider the example of Hollywood. Originally, the moviemaking industry decided to plop down in Los Angeles because the city afforded dry, sunny weather and dramatic terrain that made outdoor shooting ideal. Modern filmmaking no longer requires these natural features, but Hollywood has remained Hollywood. Why? Actors, directors, producers, and film technicians all live and work there. Locating in Los Angeles means a film studio has access to the sorts of niche labor markets and knowledgeable contractors that are required to produce movies. Want Steven Spielberg to direct your movie? Then shoot it in Los Angeles, where he and a plethora of other film industry stalwarts already live.

This is one reason why other areas have failed to jumpstart a “Second Hollywood” by providing tax incentives for film production—the original Hollywood already has inherent advantages that are very difficult to replicate.

The same phenomenon is at play in Silicon Valley. The proximity of Stanford University and U.S. Navy bases made the area a natural breeding ground for technology firms. Now, the tech industry thrives because of a large population of programmers and venture capitalists. The skilled workforce can easily move from company to company, promoting healthy competition and the sharing of ideas. Recreating that external infrastructure in Atlanta, rather than having Atlanta focus on the industries where it has its own comparative advantage, makes very little sense.

This is not to say that other cities are economic deserts—far from it. Atlanta, for instance, has thriving healthcare and media industries, and manufacturing is making a comeback there. Even the tech industry has proven it can thrive outside of California, most notably in Texas. Problems occur, however, when policymakers attempt to force this development upon cities rather than letting local economies follow their natural courses.

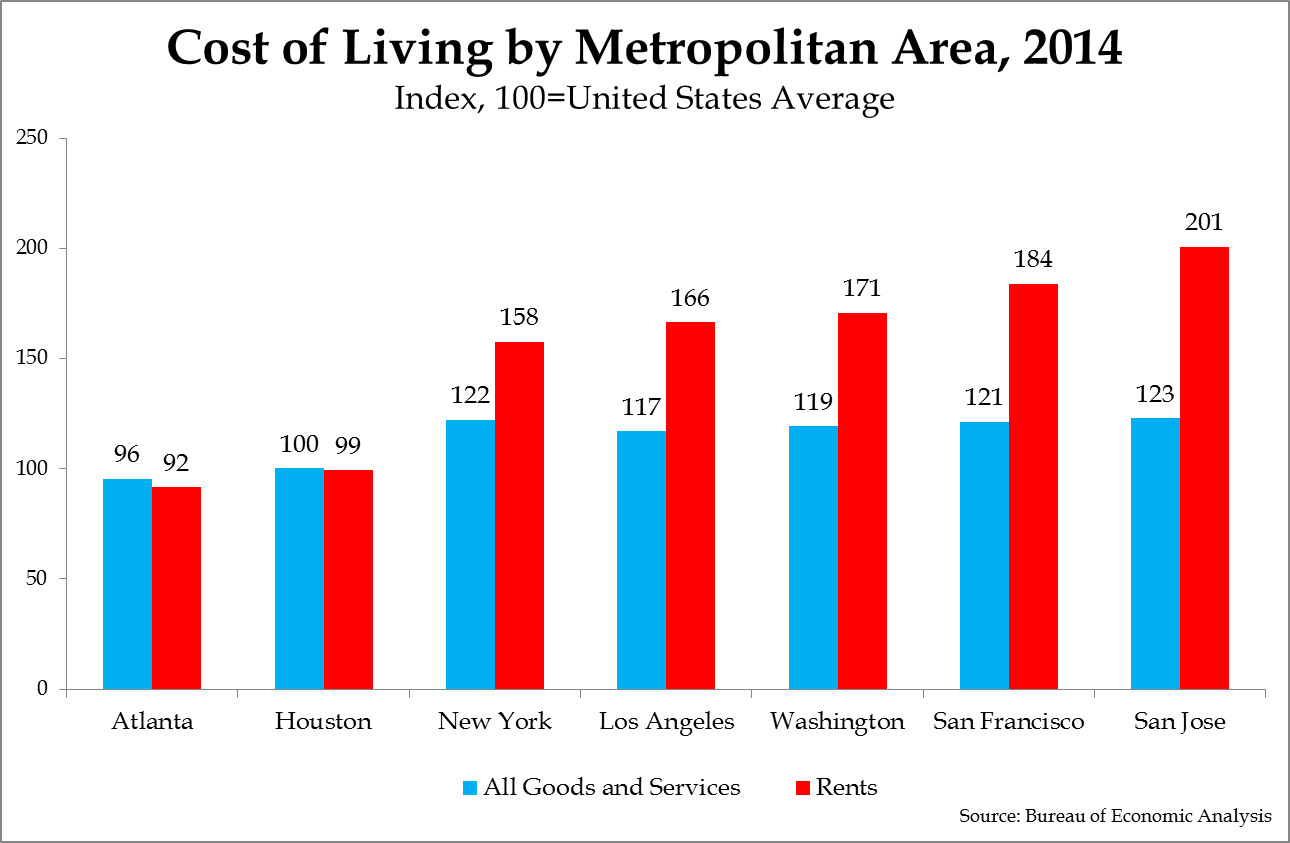

What does all this have to do with land-use restrictions? Artificially high rents discourage skilled workers from moving to the Bay Area. While technology firms pay high nominal salaries to attract them, the soaring cost of living means the real value of these salaries is moderate. This attracts fewer workers to the area, and Silicon Valley cannot achieve its optimal size. Tech firms can try locating in other cities, but they will start out with a penalty because they will be away from the common advantages that the Bay Area affords.

Productivity suffers as a result. A study last year by economists Chang-Tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago and Enrico Moretti of UC-Berkeley estimated that land-use restrictions lowered the nation’s GDP by nearly 14 percent since 1964. According to the study, the cities with the most overzealous zoning laws are, unsurprisingly, New York, San Francisco, and San Jose.

Sen argues that low real salaries in these cities show their native industries are not quite as productive as they seem, and therefore relaxing zoning laws to lower rents and attract more workers will not boost output. But it is not that Silicon Valley’s workers are not productive—rather, their real earnings do not match the full value of their output because high prices mean paychecks do not go very far.

Trying to turn Atlanta into the next Silicon Valley by fiat is more difficult than it seems. New technology firms in the Peach State will have to contend with the lack of a shared pool of skilled labor that keeps fresh talent and ideas flowing in. Atlanta’s venture capitalists have less familiarity with the tech industry than do Silicon Valley’s, and may be more reluctant to back new companies. All this means that Atlanta’s artificial Silicon Valley will be less productive than the original Silicon Valley, lowering economic growth. Atlanta’s native industries, where its comparative advantages are greater, will also suffer if they must compete for resources with Silicon Valley expatriates.

Atlanta, Houston, and the rest of America’s cities should allow their own industries to develop, rather than play copycat off the successes of San Francisco and New York. This does not necessarily mean technology or finance companies can never exist outside of their natural homes. It only means that governments should be neutral regarding such questions. Intentionally raising the cost of living in some cities in order to chase innovators away to others is no way to approach economic policy.

Preston Cooper is a policy analyst at the Manhattan Institute. You can follow him on Twitter here.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, E21 delivers a short email that includes E21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the E21 Morning Ebrief.