Like many parents, sometime in the early spring of 2020 I reluctantly began a second career as the principal and primary teacher of a small elementary school located in the living room. My kids’ teachers did their best to put together something sort of like instruction. But it clearly wasn’t enough. I lacked the tools necessary to teach them, so I spent hours online searching for ideas and downloading resources. Pretty soon we had books, worksheets, and tablets filled with learning apps. I have no doubt that without my active participation, my kids wouldn’t have made any real academic progress during this key part of their educational lives. They may have even lost ground.

My experience isn’t unique among parents during the pandemic, but I have it better than most. My family has sufficient means to acquire supplemental educational materials without batting an eye. And as a tenured university professor, my job is safer and more flexible than those of most professionals, let alone the average American, so I could afford to spend time and resources developing learning opportunities for my kids.

The disruption in schooling caused by the global pandemic will have consequences for student learning across the board. But there’s little doubt that the harm will be disproportionately felt by children in lower-income households, just as the disruption of the labor market disproportionately impacted lower-wage workers.

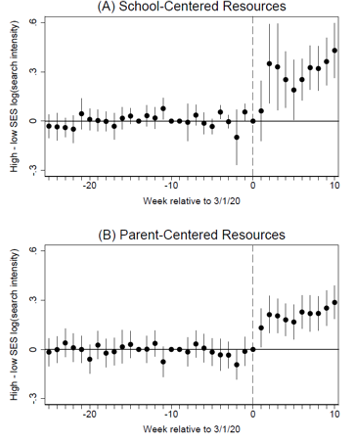

A timely paper by Andrew Bacher-Hicks, Josh Goodman – my new colleagues at the Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development – and RAND’s Christine Mulhern offers some new insights into how resources available in each home will likely exacerbate educational inequalities in a world where kids can’t go to school. They tracked weekly Google search intensity for educational materials within the U.S. overall and separately by geographic market areas before and after March 1st, when districts started shutting schools in droves. They show that in response to the sudden move to remote schooling, parents in higher-income areas searched more intensely for materials to aid their child’s learning than did parents in lower-income areas. By mid-March, the increase in search intensity for such resources was about 30 percent higher in high-SES areas than in low-SES areas.

The above figures illustrate the intuition behind their findings. The dots show the weekly difference in Google search intensity for online educational resources within high- and low-SES areas relative to the first week of March 2020 when schools started to shut down in large numbers (the whiskers show the 95% confidence interval). When the dot is at the zero-point the difference in search intensity within high and low-SES areas is the same as it was the week of March 1. The top panel shows searches for school-centered resources such as “Google Classroom” and “Khan Academy,” while the bottom panel shows more general parent-centered searches like “online learning” and “math worksheet.”

The relative search intensity for educational terms within high- and low-SES areas was very consistent for each of the more than twenty weeks leading up to the beginning of March. Then, right as schools began closing, suddenly these searches become much more common in high-SES areas, as illustrated by the sudden and sustained jump to the right of the dashed line.

This phenomenon has almost certainly continued throughout the haphazard return (or not) to school – anyone else Googled private schools recently? Perhaps more importantly, the authors offer a unique illustration of the dynamics that we’ve always known are in the background: parents use their available time and resources for their kids, but not everyone has the same time and resources available. There’s nothing nefarious about helping your kids. But the pandemic experience highlights just how essential it is provide kids from lower-income households with high-quality educational opportunities; they simply don’t receive the same resources and attention to their schooling at home as their higher-SES peers.

Marcus A. Winters is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and an associate professor at the Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. Follow him on Twitter here.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.

Photo by Lisa Maree Williams/Getty Images