China’s outsized growth in the last two decades has lifted it to the second largest economy in the world, a truly outstanding accomplishment (Charts 1 and 2). Its current target for real GDP growth—6.5%—is above its slowing potential and unsustainable. It’s unrealistic to expect China to continue to grow three times faster than advanced nations.

Chart 1: China’s Extraordinary Growth

Chart 2: Real GDP Growth, International Comparisons

Importantly, China’s unit labor costs have increased dramatically, both in absolute terms and relative to those of other nations (Chart 3). While its productivity has risen substantially, wages have increased much faster. This is particularly true in China’s eastern provinces where most of its export-related manufacturing occurs. This is cutting into China’s international competitive advantage at the same time that its sheer size is naturally slowing the pace of growth.

Chart 3: China’s Unit Labor Costs Have Risen Sharply

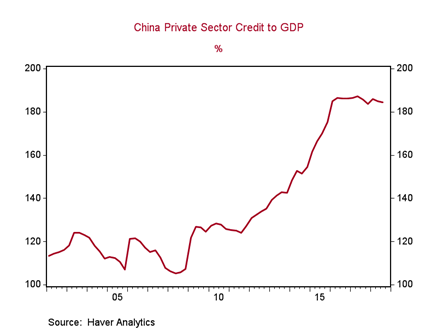

In order to maintain growth above slowing potential, more and more monetary and fiscal stimulus will be required, as well as more reliance on credit and debt. China’s policymakers have had an increasingly difficult time achieving their economic growth targets while constraining the negative implications of rising debt burdens and related excesses (Chart 4). Several years ago the People’s Bank of China and China’s Banking Regulatory Commission tightened monetary and credit policy in an effort to remove some credit excesses and housing speculation. This year, growth has slowed more than desired. The policy response has been to ease money and credit and move toward more fiscal stimulus. So far, the economy has not responded and most signals point toward further moderation in growth.

Chart 4: China’s Debt Burdens Are High

For example, surveys of household and business confidence have dipped and key indicators of domestic demand and production have slowed. Production in secondary industries that include manufacturing, production and supply of electricity, gas and water, construction and mining have slowed sharply (Chart 8). The weakness in consumption has been pronounced in auto sales, which have fallen for four consecutive months and are now down sharply, by 12% year over year (Chart 9). In response, China‘s top economic regulator has proposed a tax cut for auto purchases.

China’s slowdown is significant for the global economy because it is the world’s largest trader and is the key driver of global trade—and for many nations, a key support of healthy growth (Chart 5). While China has been very successful transitioning its economy to rely more on domestic consumption and services, exports are still 18% of GDP, and China accounts for nearly 12% of total global trade. Through August, the last observation of composite data, total global trade volumes continued to rise to an all-time high, despite widespread concerns about tariff-related disruptions and uncertainties (Chart 6). We anticipate trade volumes to decline from that peak.

Chart 5: China’s Emergence as Dominant Trader

Chart 6: Global Trade Volumes

China’s economy is critically important to Asia and many emerging market (EM) nations that trade with China and supply it with critical commodities and materials. Some advanced nations also rely heavily on exports to China. Table 1 shows China’s biggest trading partners. China is the largest trading partner for Japan, South Korea and most Asian nations. Among EM nations, Brazil has very large export exposure to China. Among advanced nations, Germany stands out with very large reliance on China’s markets. All advanced nations rely on exports to EM nations. China relies heavily on imports of both consumer goods (including motor vehicles and parts) and machinery and other durable goods used in production processes.

Table 1: China’s Goods Trade by Country

For these reasons, a moderation in China’s growth—not a hard-landing or recession, which are not expected, but simply a slowdown in both domestic demand and export-related manufacturing—would have a material impact on Asian and global trade and economies. For some—particularly Germany and Europe, which are struggling with local economic issues—a slowdown in China comes at a bad time. For other economies that are enjoying healthy above-potential growth, particularly the U.S., the ripples from a China slowdown would dampen momentum.We are already seeing signs of this. German exports of motor vehicle and parts to China and worldwide have fallen since May, and its exports of capital goods are also falling. Japan recorded a sharp fall in exports of goods and services in the third quarter that contributed to a quarterly decline in real GDP. And the United States has seen its second consecutive month of a sharp decline in export orders.

This brings us to the Trump administration’s policies toward China. Amid concerns about Trump’s imposition of tariffs, year-over-year growth of China’s real GDP has been sustained so far this year at the 6.5% target—and China’s exports and imports have continued to rise rapidly while domestic demand has begun to weaken. The sustained strong increases in China’s trade data in recent months likely reflect an acceleration of shipments in anticipation of the imposition of tariffs (Chart 7).

Chart 7: China’s Exports and Imports

Chart 8: Growth in China’s Secondary Industries

*Mining and quarrying (except auxiliary activities of mining and quarrying), manufacturing (except repairs for metal products, machinery and equipment), production and supply of electricity, steam, gas and water, and construction

But Trump’s aggressive negotiating tactics come at a very bad time for China, as its economy is showing more stresses and its leaders are under pressure on several glaring social issues. A weakening economy undercuts the leaders’ popularity. China’s leaders are aware that potential growth is moderating, but they are reluctant to lower their target GDP growth. Eventually, they will do so.

My colleagues and I expect an eventual agreement on U.S.-China trade that will ease tensions on tariffs and will include many changes: China will agree to open up some of its markets to imports of select U.S. products and modify some of its practices with intellectual properties and provisions relating to direct foreign investment and joint venture projects in China in exchange for the United States easing its recent imposition of tariffs. An eventual broad agreement is also expected to include agreements on select issues that go way beyond economics and trade, such as U.S. concerns about cybersecurity and tensions in the Asia region. China desperately needs to maintain trade channels with the U.S., its largest trading partner, and Trump is a tough negotiator who has shown a pattern of threatening (or imposing) tariffs as leverage, which are repealed to achieve concessions. Whether anything material is really accomplished hinges on the details, many of which will be non-economic in nature.

Chart 9: Growth in China’s Secondary Industries

A current issue is what will break the ice between China and the United States to facilitate a broader trade agreement. Our hunch is China will be willing to enter a long-term agreement to import substantial amounts of liquefied natural gas from the United States. China is the world’s biggest importer of natural gas and its demands are projected to grow significantly, particularly as it aims to reduce its reliance on coal. It relies way too much on Russia for its natural gas supplies. The U.S.’s marginal cost of extracting natural gas is close to zero—because it is a bi-product of oil/shale drilling—and the U.S. is very quickly building and improving pipelines and transshipment ports that will facilitate low-cost distribution.

While volumes of U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas to China would be relatively small in the intermediate term, long-term projections would show increases sufficiently large to make a dent in the U.S.’s bilateral trade deficit with China. Such an agreement would be perceived to be a win-win for both China and the U.S. (while undercutting Russia’s negotiating power with China). But this would be only one component of a U.S.-China agreement, and the details of any broader agreement would determine its efficacy.

Mickey Levy is the chief economist for the United States, the Americas, and Asia at Berenberg Capital Markets, LLC and a member of E21's Shadow Open Market Committee (SOMC). The views expressed in this column are the author’s own and do not reflect those of Berenberg Capital Markets, LLC.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.